MYANMAR

Myanmar Be Enchanted

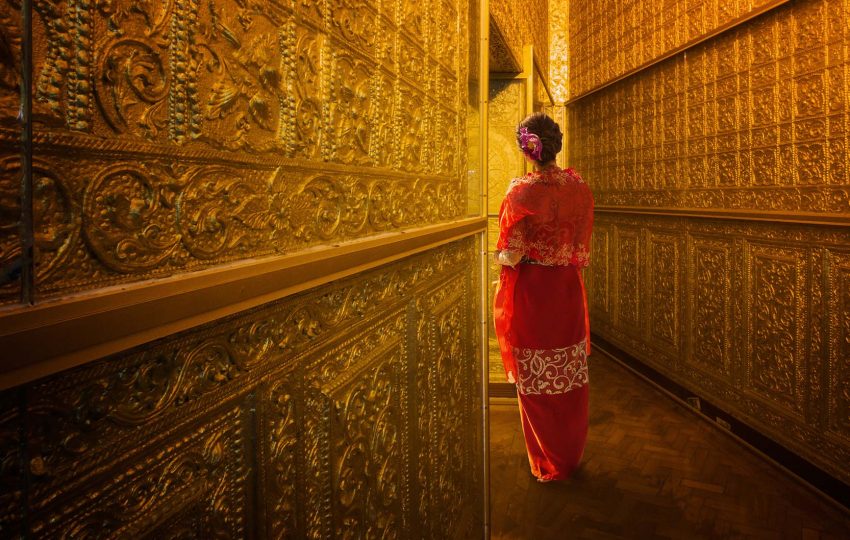

Being a country full of intriguing history and tradition, Myanmar is slowly becoming an extremely popular destination to visit. With ancient temples and pagodas, untouched landscapes, and an emerging culture that is slowly opening up to the modern world, there is much to learn and discover about this place.

When choosing a holiday to Cambodia, the main reason for traveling is, of course, Southeast Asia’s most magnificent archaeological treasure – The Angkor Wat Complex with hundreds of ruins and history, hidden deep in the jungle and telling stories about the past.

Top destinations

Top Activities

our unique tours

Myanamar Travel

Myanmar has a tropical climate, with the southwest monsoon bringing rain from May to October. Roads can become impassable, particularly from July to September. The central plains, however, receive only a fraction of the rain seen on the coast and in the Ayeyarwady delta. From October onwards the rains subside; the best time to visit most of Myanmar is from November to February, when temperatures are relatively manageable. From March to May, the country becomes very hot, particularly the dry zone of the central plains where Bagan and Mandalay often see temperatures in excess of 40°C.

Festivals and Holidays in Myanmar

Most festivals in Myanmar are based on the lunar calendar; check the official Ministry of Hotels & Tourism site for a more extensive list (myanmartourism.org/festivals.htm).

Shwedagon Festival

Feb/March. The country’s biggest paya pwèh (temple festival) takes place at Shwedagon Paya in Yangon.

Thingyan

April 13–16. The water festival is the most popular in the calendar, marking New Year with a good soaking as temperatures soar. It also has a spiritual side, as it’s when the nat king visits the human world to record good and bad deeds. Hotels and transport are often booked solid.

Fire Balloon Festival

Nov. Daytime parades at this three-day event in Taunggyi, east of Inle Lake, include impressive animal-shaped hot-air balloons. At night, balloons are released with huge gondolas full of fireworks strapped underneath them, sometimes with predictably explosive results.

Shan New Year

Dec. Keep an eye open for the different ethnic groups’ new year celebrations around Dec and Jan. This one rotates between different Shan towns, and includes live bands, traditional dancing and – on Shan New Year’s Eve itself – fireworks and an inclusive party atmosphere.

Ananda Pahto festival

Dec/Jan. The paya pwèh at Ananda Pahto is the biggest in Bagan, running for the fortnight leading up to the full moon of Pyatho. For the last three days, hundreds of monks chant scriptures day and night.

All foreign nationals require a visa in order to visit Myanmar. Although a visa-on-arrival system does exist, it applies only to business visitors or conference guests who are able to provide documents such as letters of invitation.

You will therefore need to obtain a tourist visa from a Myanmar embassy or consulate before you travel to the country, as you will not be able to get one at the border. In order to apply, your passport must be valid for at least six months from your proposed date of arrival. Tourist visas typically last for 28 days from the date of entry, which must be within three months of issue, and cost around $20–30. Some embassies, such as the one in Bangkok, offer same-day service for an additional cost.

Tourist visas cannot be extended, but it is possible to overstay them. A fee of $3 per day of overstay (plus, sometimes, an additional $3 for “administration”) will be collected on departure at the airport, before you are stamped out of the country. Visitors have reported overstaying by three weeks or more without officials at the airport raising any objections. The only possible hitch is that guesthouses occasionally express concern with expired visas, although it is rare to hear of accommodation actually refusing to allow people to stay.

With overland border crossings close to impossible for independent travellers, almost everyone arrives in Myanmar at either Yangon or Mandalay airports. There is also an international airport in the capital Nay Pyi Taw, although few airlines use it at present. The international flag carrier, Myanmar Airways International, only serves destinations within Asia.

The cheapest way to reach Myanmar from outside the region is usually to fly to a regional hub such as Bangkok or Singapore. Current routes within Asia include flights to Yangon from Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and Bangkok. Connections with Mandalay are limited to Dehong, Kunming and Bangkok.

Overland from Thailand

There are four border crossings with Thailand: Ranong–Kawthaung; Three Pagodas Pass (Sangkhlaburi–Payathonzu); Mae Sot–Myawaddy; and Mae Sai–Tachileik. It is possible to make a day-trip to Myanmar through any of them for a fee of $10 or 500 baht, but if you’re just crossing on a visa run then don’t choose Three Pagodas Pass as you will not get a new Thai visa stamp on re-entry. If you want to take a look around before returning to Thailand then you will need to surrender your passport at the border and return before the crossing closes for the day (usually at 6pm, but do check).

If you hope to spend more than a day in Myanmar then it is theoretically possible when entering through Ranong–Kawthaung and Mae Sai–Tachileik, but not with a standard visa. For the former crossing, you’ll need a special permit, which in practice is impossible to obtain unless you have booked an expensive resort or a live-aboard diving trip. For the latter, you can arrange a fourteen-day permit at the border, but it does not allow travel beyond Kengtung. You are also likely to require a local guide.

Tachileik–Mae Sai is also the only overland crossing where foreigners who entered by air are allowed to exit Myanmar, but it isn’t at all straightforward. Although it’s easy to obtain a free permit to visit the border town of Tachileik (apply at the immigration office in Kengtung), actually crossing into Thailand requires prior arrangement with Myanmar Travels & Tours (the government tourist office) in Yangon. You should not rely on it being possible until you actually have the permit in hand; expect the process to take a couple of weeks and cost at least $50, plus you may be required to take a local guide to the border. If it all works out then you should receive a fifteen-day visa on arrival into Thailand, if you don’t already have one.

Overland from China

There is a border crossing open for foreigners between Ruili (Yunnan province) and Muse. For some years it has only been open to organized tour groups, although there are rumours that it is due to be opened to independent travellers.

Overland from India

The crossing between Moreh in India and Tamu is theoretically open to foreigners, but onerous permit requirements – which take several months to negotiate, if you’re lucky – mean that it is not a feasible route.

Overland from Laos or Bangladesh

It is not currently possible for foreigners to cross from Laos or Bangladesh into Myanmar.

Planes

In addition to Myanma Airways, the state-owned national flag-carrier, an array of private airlines – among them Air KBZ, Air Mandalay, Air Bagan, Asian Wings, Yangon Airways and Golden Myanmar Airlines – run services on domestic routes and have offices in major towns and cities. Given the long journey times overland, and the relatively low prices of flight tickets, travelling by plane can be an attractive choice. In a few cases, such as visiting Kengtung, it is the only option as overland routes are closed to foreigners. Many services fly on circular routes, stopping at several airports on the way. At each stop, some passengers will get off, some will get on, and some will stay on board and wait for a later stop. One quirk of this is that it may be easier to make a journey one way (for example, Nyaung U to Thandwe) than the other way (Thandwe to Nyaung U).

There are a number of downsides to domestic air travel. For one thing, it may not save you much time as schedules are subject to change at short notice and delays are not uncommon. It also isn’t possible to buy tickets online, although some airlines – such as Air Mandalay – allow online reservations and you then pay once you’re in the country. This is likely to change following the easing of sanctions, but in any case it’s generally a bit cheaper to buy tickets through local travel agents. In addition, travellers should avoid flying if they are trying to limit the amount of their money that ends up with the government or its cronies (see The Ethics of visiting Myanmar).

Buses

Most long-distance buses are reasonably comfortable, but make sure you bring warm clothes as they tend to crank up the air-conditioning. On major routes, such as Yangon to Mandalay, it’s possible to take a more modern bus for a small additional fee. There are also local buses running segments of longer routes, such as Taungoo to Mandalay (rather than the full Yangon-to-Mandalay trip); these are usually in worse condition but are cheaper for shorter trips, as on long-distance buses you pay the fare for the full journey even if you get on or off partway through. You’ll also find smaller, 32-seat local buses that should be avoided if possible, as they tend to be jam-packed with luggage.

It’s a good idea to book a day or two ahead for busy routes (eg Bagan–Nyaungshwe), ones where only a few buses run (eg Ngwe Saung–Yangon) or where you’re joining a bus partway through its route (eg in Kalaw).

Guesthouses can often help book tickets for a small fee, or you can buy them either from bus stations (which in some cases are outside of town) or from in-town bus company offices.

Trains

The railway system in Myanmar is antiquated, slow and generally uncomfortable. On most routes a bus is faster and more reliable – it is not uncommon for express trains to be delayed by several hours, and local trains are even worse. Trains are also more expensive than buses, and since they are state-run, the money goes to the government. All that said, there are reasons why you might want to take a train at least once during your trip. One is that on a few routes, such as from Mandalay up to Naba and Katha, road transport is closed to foreigners. Another is for the experience itself: many routes run through areas of great beauty (the Goteik viaduct between Pyin Oo Lwin and Hsipaw is a good example), plus there is the chance to interact with local people.

All express trains have upper- and ordinary-class carriages. The former have reservable reclining seats, while the latter have hard seats and no reservations. Some trains also have first-class carriages, which fall somewhere between upper and ordinary in price and comfort. Sleeper carriages, when available, accommodate four passengers and come with blankets and linen.

Long-distance trains often have restaurant cars, and food vendors either come on board or carry out transactions through the windows whenever the train stops. The bathrooms onboard are basic and often unclean.

Fares are payable in US dollars and vary according to class, although you may find station staff are reluctant to sell ordinary-class tickets to foreigners. Try to reserve a day or so in advance, or more for sleepers.

Shared taxis and vans

Although not as common as in some Southeast Asian countries, shared taxis and shared vans (the latter also known as minibuses) are available on some routes. Shared vehicles charge separately for each seat and leave once full, making them cheaper than taking a whole taxi. They typically cost around fifty percent more than a seat on an air-conditioned bus, but will drop you wherever you like, which saves on transfer costs in towns where the bus station is inconveniently located. Vehicles can sometimes be arranged through accommodation, and there are sometimes shared-taxi stands in town centres.

In addition to these services between towns, which are primarily used by locals, there are a handful of services aimed specifically at foreigners. These are typically round trips, such as to Mount Popa from Bagan.

Car, bike and motorcycle rental

There are numerous hazards for motorcyclists: traffic can be very heavy in the cities, while in rural areas the roads are often in poor condition. Adding to these dangers is the fact that most cars are right-hand drive even though people drive on the right, meaning that cars have large blind spots. Overtaking is, as a result, a pretty risky manoeuvre. Before hiring a motorbike, check that your travel insurance covers you for riding one.

Local transport

Most of these forms of transport can also be hired for a day including a driver, which can be arranged direct, through accommodation or via travel agents; you’ll need to bargain to get a good price. Motorcycle taxis are popular in this regard, particularly for solo travellers, and may not work out much more expensive than hiring a self-drive motorcycle. Groups can often get a good deal on a pick-up for the day, for example in one of the “blue taxis” of Mandalay.

In small towns, horse carts are used as a key form of transportation, and are used to ferry tourists around in a number of places, notably Bagan, Inwa and Pyin Oo Lwin. The horses are not always well looked after, however.

While people in Myanmar take great pride in their cuisine, if you ask someone for a restaurant recommendation then there’s a good chance that they will suggest a place serving Chinese food. This is partly because they worry that foreign stomachs can’t cope with Burmese food, but also because most people rarely eat at restaurants so when they do they eat Chinese as a treat. Most towns will have at least a couple of Chinese restaurants, typically with large menus covering unadventurous basics such as sweet and sour chicken. Dishes start at around K1000 (vegetables) or K1500 (meat). Indian restaurants are also popular, particularly in Yangon which had a very large Indian population during the British colonial era. In tourist hotspots you’ll also find restaurants serving Thai and Western (usually Italian) dishes.

One local tradition that has become an essential tourist experience is a visit to a teahouse. These are hugely popular places to meet friends, family or business associates over tea and affordable snacks, which, depending on the owners, might be Burmese noodles, Muslim samosas or Chinese steamed buns. Teahouses have long had a reputation for being places where politics can be openly discussed, although there have always been rumours of government spies observing. Some teahouses open early for breakfast, while others stay open late into the night.

Burmese food

As in other Southeast Asian countries, in Burmese food it’s considered important to balance sour, spicy, bitter and salty flavours; this is generally done across a series of dishes rather than within a single dish. A mild curry, for example, might be accompanied by bitter leaves, dried chilli and a salty condiment such as fish paste.

The typical local breakfast is noodle soup, such as the national dish mohingar (catfish soup with rice vermicelli, onions, lemongrass, garlic, chilli and lime, with some cooks adding things like boiled egg, courgette fritters and fried bean crackers). Alternatives include oùn-nó k’auq-s’wèh (coconut chicken soup with noodles, raw onions, coriander and chilli) and pèh byouq (fried, boiled beans) served with sticky rice or naan bread. All of these dishes are served in teahouses or available to take away from markets.

There are plenty of regional variations to discover as you travel: the food of Rakhine State, for example, is influenced by its proximity to Bangladesh, so curries are spicier and many dishes include beans or pulses.

Drinks

Although there are few places resembling Western bars or pubs outside of Yangon and Mandalay, most towns will have a couple of beer stations which look like simple restaurants but with beer adverts on display and a predominantly male clientele. These places usually serve draught beer (around K700 for a glass) as well as bottles (from K1700 for 640ml), with the former usually restricted to the most popular brew, Myanmar Beer (produced by a government joint venture) and sometimes its rival Dagon. Both beers are also available in bottles, as are Mandalay Beer and several Thai and Singaporean beers, including Tiger, Singha and ABC Stout.

Mid-range and upmarket restaurants will often have a list of imported wines. There are a couple of vineyards making wine in Shan State, and it’s better than you might expect: look out for Red Mountain and Aythaya. Fruit wines are produced around Pyin Oo Lwin, while local spirits include t’àn-ye (toddy or palm wine).

Trekking

Opportunities for treks are limited by two main factors. One is that many of the most appealing areas are in the mountainous border regions, which tend to be closed to tourists. The other is that foreigners are generally expected to stay in licensed accommodation for every night of their visit. Camping is illegal as, in most parts of the country, is staying in local homes.

As a result, day-hikes are the limit in many places. In Kengtung, for example, there are some excellent walks to ethnic minority villages but you cannot stay in any of them overnight. There are exceptions, however, with the most notable being around Kalaw, Inle Lake, Pindaya and Hsipaw. In these areas it’s possible to stay in either homes or monasteries, by prior arrangement through a tour agency, and therefore do multi-day treks. It’s still unusual for people to trek for more than three days. A guide is strongly recommended for most hiking, although the trails around Hsipaw are often undertaken without one. In some places, such as Kengtung, a guide is obligatory.

Biking and motorbiking

Both mountain biking and motorbiking tours are available in Myanmar, through specialist agencies. There are many advantages to getting around in this way, not least the chance to interact with people in villages and rural areas; disadvantages include having to put up with the poor state of many roads, plus the requirement to sleep in licensed accommodation which means that you cannot be as flexible or spontaneous as you might like. Some cyclists have used camping as a back-up, but it is, strictly speaking, illegal and should not be relied upon.

Diving and watersports

For a country with such a long coastline, there are very few water-based activities in Myanmar. Scuba diving is offered at Ngapali beach and the Myeik (Mergui) archipelago, neither of which are budget destinations.

Meditation

With a strong and long-held Buddhist tradition, Myanmar is a good place to learn to meditate. Some centres will only take foreigners who commit to staying for several weeks, but one shorter option is a ten-day course in Vipassana meditation at a centre in Yangon on Nga Htat Gyi Pagoda Road, close to Shwedagon Paya.

As in other Southeast Asian countries, clothing in Myanmar is usually modest. In some ethnic minority villages it’s still the norm to wear traditional dress, and even in cities many men and women wear a traditional skirt-like garment called a longyi. These days, though, it is also common for locals to wear Western-style clothes and you’ll very occasionally see men in shorts. People will be too polite to say anything, but they may be offended by the sight of tourists wearing revealing clothes. This would include shorts cut above the knee, and – particularly for women – tops that are tight or show the shoulders. It’s especially important to dress conservatively when visiting temples, and some travellers carry a longyi for such situations.

Most women and girls, as well as some men and boys, use thănăk’à (a paste made from ground bark) on their faces; traditionally thought to improve the skin and act as a sunblock, it is often applied as a circle or stripe on each cheek.

Avoid touching another person’s head, as it is considered the most sacred part of the body; feet are unclean and so when sitting don’t point your feet at anyone or towards images of the Buddha. Remove your shoes before entering a Buddhist site or a home. Always use your right hand when shaking hands or passing something to someone, as the left hand is traditionally used for toilet ablutions; however, locals do use their left hand to “support” their right arm when shaking hands.

Most people in the country are Buddhist although there are significant Muslim and Christian minorities. Men are expected to experience life in a monastery twice in their lives, once when a child and once as an adult, although this is only for a short time unless they become a novice. Most Buddhists also believe in nats, spirits rooted in older animist traditions, which are now considered to be the Buddha’s disciples. These supernatural beings take an interest in the actions of humans, and may need to be propitiated.

Considering the social conservatism of Myanmar’s society it is interesting to note that while in the past most nat kădaws (spirit mediums) were women, today most are gay men and many are either transgendered or transvestites. A nat-pwèh (spirit festival) held, for example, at the start of a new business enterprise is an occasion on which people have license to sing, cheer and show emotions which would otherwise be repressed in public. Homosexuality is, however, technically illegal in Myanmar – for tourists as well as locals – and punishable by fines or imprisonment, but this is rarely enforced in practice. There is a discreet gay scene in Yangon, but little elsewhere.

capital

Yangon

popularityPopulation

Over 55mil

curency

Kyat (K)

biggest city

Yangon

language

Myanmar language

best time to vist

Nov - Feb

Lastest News

Plan Your Trip!

Let us transform your dreams into the ultimate vacation experience. Our consultation and itinerary design services are complimentary until you are completely satisfied with the proposed program. We design; you decide.